The landmark decision could transform the treatment of sickle-cell disease and β-thalassaemia — but the technology is expensive.

In a world first, the UK medicines regulator has approved a therapy that uses the CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing tool as a treatment. The decision marks another high point for a biotechnology that has been lauded as revolutionary in the decade since its discovery.

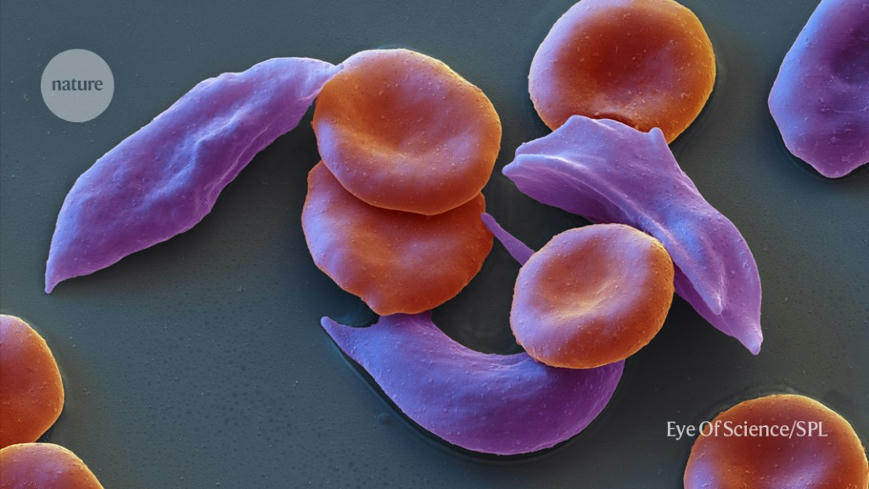

The therapy, called Casgevy, will treat the blood conditions sickle-cell disease and β-thalassaemia. Sickle-cell disease, also known as sickle-cell anaemia, can cause debilitating pain, and people with β-thalassaemia often require regular blood transfusions.

“This is a landmark approval which opens the door for further applications of CRISPR therapies in the future for the potential cure of many genetic diseases,” said Kay Davies, a geneticist at the University of Oxford, UK, in comments to the UK Science Media Centre (SMC).

Nature magazine explains the research behind the treatment and explores what’s next.

What research led to the approval?

The approval by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) follows promising results from clinical trials that tested a one-time treatment, which is administered by intravenous infusion. The therapy was developed by the pharmaceutical company Vertex Pharmaceuticals in Boston, Massachusetts, and biotechnology company CRISPR Therapeutics in Zug, Switzerland.

The trial for sickle-cell disease has followed 29 out of 45 participants long enough to draw interim results. Casgevy completely relieved 28 of those people of debilitating episodes of pain for at least one year after treatment. Researchers also tested the treatment for a severe form of β-thalassaemia, which is conventionally treated with blood transfusions roughly once a month. In this trial, 54 people received Casgevy, of which 42 participated for long enough to provide interim results. Among those 42 participants, 39 did not need a red-blood-cell transfusion for at least one year. The remaining three had their need for blood transfusions reduced by more than a 70%.

Read the full article at: www.nature.com