No one had ever seen one virus latching onto another virus, until anomalous sequencing results sent a UMBC team down a rabbit hole leading to a first-of-its-kind discovery. It’s known that some viruses, called satellites, depend not only on their host organism to complete their life cycle, but also on another virus, known as a “helper,” explains Ivan Erill, professor of biological sciences.

The satellite virus needs the helper either to build its capsid, a protective shell that encloses the virus’s genetic material, or to help it replicate its DNA. These viral relationships require the satellite and the helper to be in proximity to each other at least temporarily, but there were no known cases of a satellite actually attaching itself to a helper—until now.

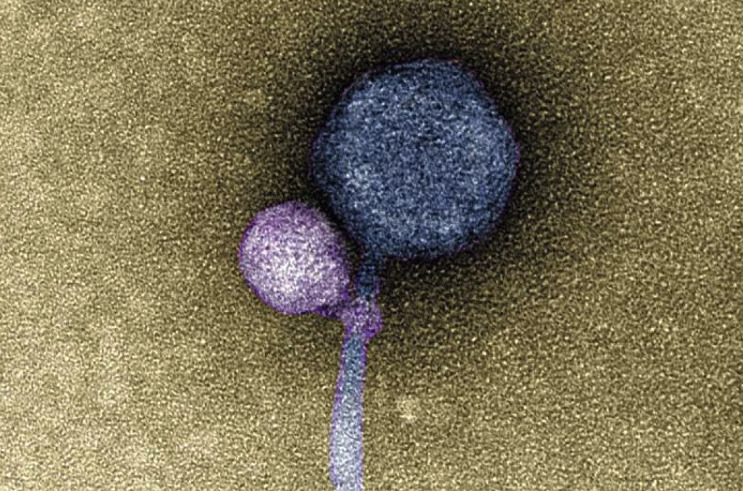

In a paper published in The ISME Journal, a UMBC team and colleagues from Washington University in St. Louis (WashU) describe the first observation of a satellite bacteriophage (a virus that infects bacterial cells) consistently attaching to a helper bacteriophage at its “neck”—where the capsid joins the tail of the virus. In detailed electron microscopy images taken by Tagide deCarvalho, assistant director of the College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences Core Facilities and first author on the new paper, 80 percent (40 out of 50) helpers had a satellite bound at the neck. Some of those that did not had remnant satellite tendrils present at the neck. Erill, senior author on the paper, describes them as appearing like “bite marks.” “When I saw it, I was like, I can’t believe this,” deCarvalho says. “No one has ever seen a bacteriophage—or any other virus—attach to another virus.”

Research is published in ISME (October 31, 2023):

Read the full article at: phys.org